Some information flows in a Samoan fono

Posted on Thu 17 February 2011 in Rumination

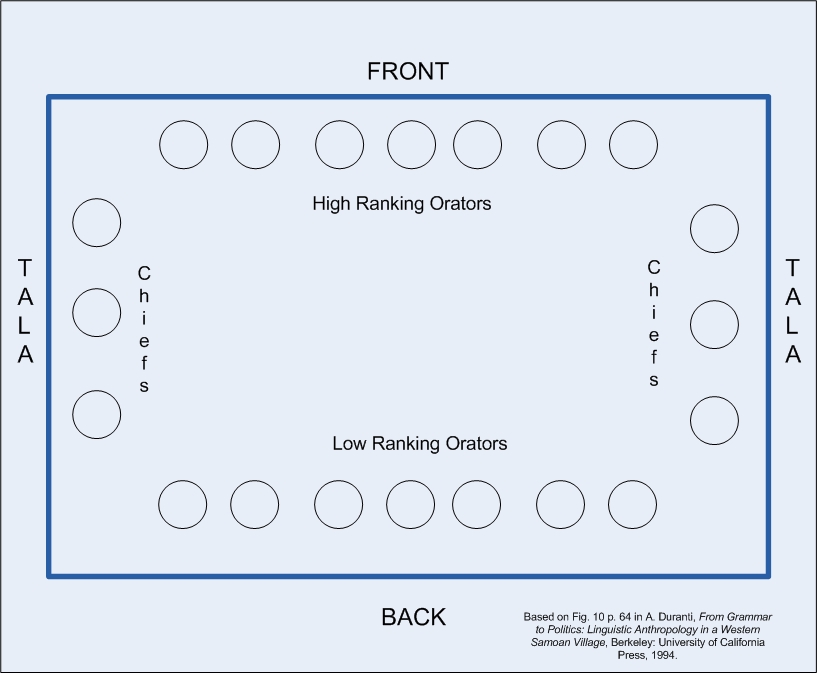

Idealized spatial organization of the fono

Idealized spatial organization of the fono

The fono, politics and space

A fono is a political meeting in the Western Somoan village. The fono is a spatially organized event: high ranking orators are seated in the front, low ranking orators and other low status and low rank persons in the back. High status chiefs and special guests are seated on the sides (tala).

A person's location with respect to these three areas during an event may signal a variety of informational contents, some of them stereotypical and some of it sensitive to the particular situational context of the event. Within each area, the position of individuals can also signal various informational contents, particularly as relating to status. The precise boundaries between these three areas may not be well defined, and seating in an ambiguously defined location may itself convey interesting information.

What enables these sorts of information to be conveyed?

Cognitive Schema of the fono

Alessandro Duranti answers this by positing a cultural cognitive schema defining an idealized fono seating arrangement spatially organized in terms of various socially relevant classes of persons:

By matching the ideal plan for a particular occasion with the actual titleholders who occupied various positions in the house, one could obtain a first reading of the political situation and make a few predictions about the way in which the discussion might unfold. Thus, according to the kind of fono that was being held, a particular set of orators would be expected to sit in the front row. In such a system, every slight variation from what is considered the ideal plan is potentially significant. For this reason, as suggested above, the ideal plan acts as a cognitive schema that provides a key for the participants to interpret the contingencies of the day. The relationship between the ideal seating arrangement and the actual one gives a first approximation of the potential conflicts, tensions, and issues of the day. (Duranti p. 65)

This schema indicates various sorts of stereotypical information. If a person p is seated in the front F then one conventional item of informational content indicated by this fact is that p is a high-ranking orator. Other informational contents are indicated too, of course. More interesting are occasions when an actual fono deviates (or is believed to deviate) from this schema. Subtle variations in seating arrangement, in conjunction with knowledge of the political situation, can indicate various interesting sorts of information. Throughout Duranti's analysis, he draws us to the subtle political dimensions of the relative positions taken up in the political theater of the fono:

Samoans are in this respect true masters of spatial finesse, as demonstrated by the poisition occupied by the matai (JL: chief) who shares the title with Savea Sione, namely Savea Savelio. He sits in a position that is similar to Savea Sione's but slightly "farther back." This he explained to me as a sign of restraint: He should not take a foregrounded role in the fono proceedings given that the actions of the one we might call his alter ego, Savea Sione, were under severe scrutiny by members of the assembly. (Duranti p. 68)

and how an intimate understanding of this space provides informational cues for contextually relevant political positioning and interaction.

An understanding of the locally engendered meaning of the seating arrangement for the day suggests that Moe'ono, as well as the other matai in the fono house, had ways of expecting, ahead of time, Tafili's attack and her role at the meeting. If she is present and has chosen to sit in the front row, the place reserved for the more active members of the assembly, everyone knows that Tafili has come ready to speak and, most likely, to argue. Thus, even before a word is exchanged, Tafili's spatial claim provided Moe'ono with clues about the forthcoming discussion and gave him some time to prepare himself for it. In this case, the regionalization of the interactional space available to participants can communicate just as much as words. (Duranti p. 72)

Information Flows

Jon Barwise and Jeremy Seligman argue that information flow crucially depends on regularities within distributed systems. Such information flows are present, but they will not necessarily be available to any particular cognitive agent nearby. Such agents must be attuned to those regularities to translate information about the occurrence of an event of one type into information about the occurrence of an event (possibly the same) of another type. This becomes particularly evident when one is displaced into natural and cultural environments outside our own experience and knowledge. One might not know, for example, that an increase in the number of insects indicates water nearby; a certain discoloration of the skin may indicate that a patient has a certain inflammatory skin disease, but only to a person attuned to the constraints between this kind of skin discoloration and the presence of that particular disease. Duranti describes his first encounter with the fono:

The first time I entered the fono house, I only saw people sitting around the eges of the house and noticed that some portions were unoccupied whereas other portions seemed crammed with people. (Duranti p. 64)

It was only after mapping many different fono events, and matching seating with titles and other relevant information, that Duranti was able to appreciate how much information about the political events of the day was present in the seating locations of its participants. Standing back from this, we must recognize that every participant in a fono is thus situated, having their own information, and being attuned to some constraints active in the situation, and not others, and so on. This is particularly easily seen when on one occasion, Duranti intentionally seated himself in a low status position in the fono, when as a guest he was usually accorded a high status position. In this case Duranti sat in the back of the fono (low status position) with low status men, and women. He was was served food last by young servers, and didn't get any fish, until one of the high status chiefs noticed and directed the servers to bring some of his fish to Duranti:

My experiment was over. I had been able to show the relevance of the locally defined spatial distinctions (front vs. back region) for establishing the status of a participant in a public event. At the same time, I had proven to myself that the system was flexible. Different "parts," namely the servers versus the matai, or the kids versus my adult friends, were acting on different premises. For the kids who brought in the trays with the food and for the untitled adults who were preparing the portions, it was safer to follow the basic spatial distinctions. They had no way of knowing the details about who was doing what on a particular occasion. The spatial arrangement in the house constituted a first key to know how to operate with a minimum assurance of appropriateness...In most cases, the seating plan works very efficiently to convey a first sense of order. Whether or not that order conforms to the relative statuses of the participants as displayed on other occasions is not something that low-status people must be concerned with. Their socialization teaches them that any hierarchy must adapt to contingencies, must fit their task...It is up to the more knowledgeable members in the gathering to complement or rectify the reading provided by the bare layout of the human bodies in space...The distribution of knowledge about how to act on any given situation is thus functional to the distribution of power within the community. On the one hand, the lower-status people act on more general and hence more easily amendable models, that is, models that need additional information in order to operate appropriately. Higher-status people, on the other hand, not only have access to more specific information about the nature of the activity and the expected and expectable actions, they also control this more specific knowledge by putting it to use when they choose to do so. (Duranti p.59-60)

The fono is a distributed system, with many different parts. Information about one part of the fono can give us information about other parts of the fono. But the information flows in this distributed system are relative to to the cognitive schemas by which the fono is conventionally understood by each of the participants. The information flows to which any participant is attuned depends on their assessments of how others are attuned to informational flows in the event. Duranti is able to assess the reasons for his not receiving any fish from the servers because his position in the fono conventionally indicated a low rank and status, and because the servers were not sensitive to other information relevant to interpreting Duranti's behavior in any other way*.

In order to see Duranti's choice of seating as an exception to the idealized arrangement presumes not only knowledge about the idealized arrangement, but crucially requires additional information that is inconsistent with that idealized arrangement. In this case, the fact that at one other such occasions Duranti had been seated toward the front. Like Duranti when he first began to participate in the fono, any stranger encountering the scene for the first time, especially one who was not familiar with the dynamics of agency and signification in the fono, would not know 'what was going on'. That Duranti was unusually seated likely would not have impressed itself on such an observer as a fact worth pondering further. But the intelligent and culturally and situationally literate observer would have seen Duranti's position as unusual, and possibly interesting, if noticed. The seating of any actual fono is set against the idealized arrangement given by the cognitive schema; the difference between them is a scaffold for signification.

Since deviation from the ideal is not infrequent, and is often interpreted this way or that, we might very well suppose that some deviations from the ideal are in fact conventional with well understood. Others less so. When Savea Savelio sits slightly back from Savea Sione, Savea Savelio, and presumably many of the other participants understood, though Duranti may not have seen the reason until later. Yet, while there may have been some conventional interpretation of Duranti's sitting in the back, it is safe to say that that interpretation of his seating misunderstood Duranti's unconventional objective. We may well doubt that anyone besides Duranti, or anyone he let in on it beforehand, correctly understood that his sitting in the back was a behavioral experiment.

*It is also possible that the servers speculated on the reasons, but did presume to act on those speculations.

Citation

A. Duranti, From Grammar to Politics: Linguistic Anthropology in a Western Samoan Village, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.